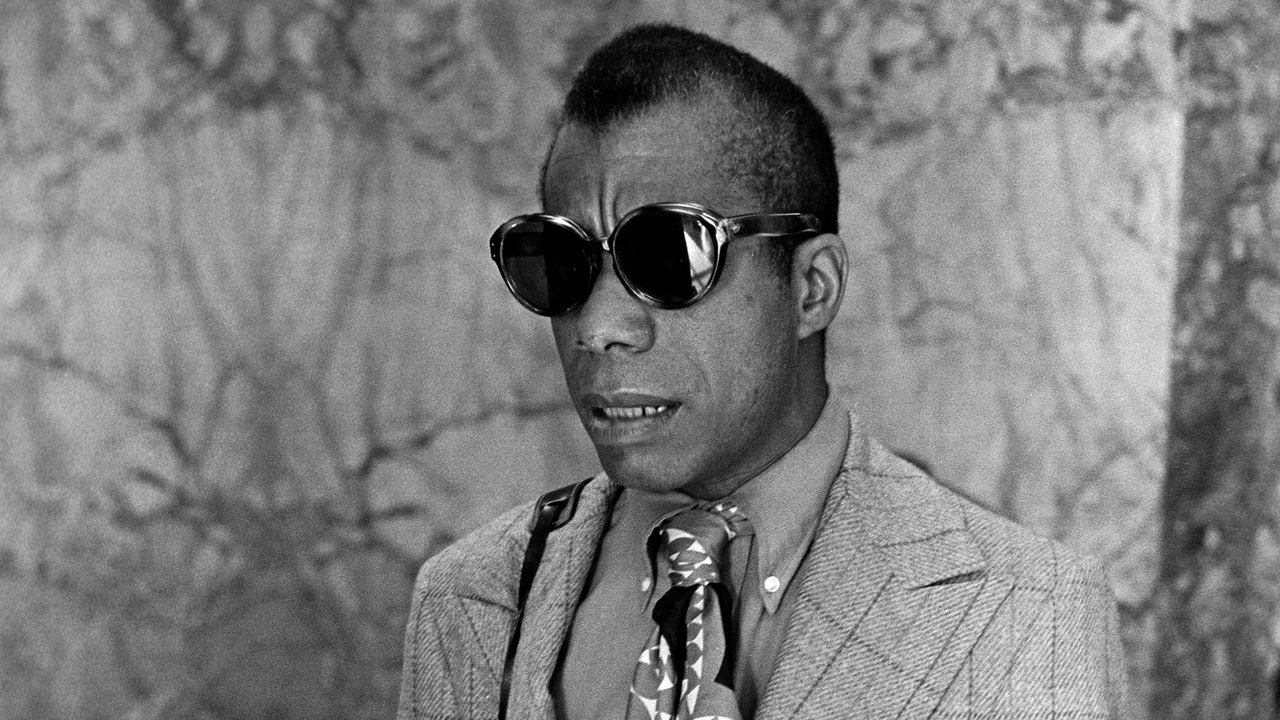

Born a era later, James Baldwin, like Hurston, didn’t put on his wounds; as a substitute, he wore sun shades. Scarves. Coats with sharp collars and clear traces. His wardrobe wasn’t extravagant, but it surely was exacting, every garment chosen like a well-placed phrase.

He dressed the best way he wrote: with rhythm and at all times in response to what the world refused to see. In New York, his style for three-piece fits echoed the cautious tailoring of the Harlem Renaissance: sq. shoulders, nice materials. Then, in Paris, he shed the burden. Within the late Nineteen Forties, the rise of racial violence and McCarthyism, which focused LGBTQ+ people through the so-called Lavender Scare, made life in america precarious for Baldwin as a Black queer man. So he fled to Paris, a longtime haven for artists like Josephine Baker and Richard Wright. There, he honed his insights on race, energy, and belonging and completed his first printed novel—1953’s Go Inform It On the Mountain—and drafted 1956’s Giovanni’s Room in addition to a number of essays in his 1955 assortment Notes of a Native Son. He additionally adopted minimalist trench coats and slim-cut fits that aligned him with the mental bohemianism of the Left Financial institution and the clear, architectural traces quickly popularized by Pierre Cardin. In a while, in Istanbul, the place he would spend a lot of the Sixties, Baldwin embraced extra fluid silhouettes, his look standing other than each the uniformed militancy of the Black Panther Celebration and the psychedelic flamboyance of the counterculture motion at house.

He by no means surrendered to full European assimilation, nonetheless. The sting of Harlem lingered: a hoop, a fitted turtleneck, the best way he stood. Baldwin wasn’t attempting to vanish, however neither did he need to be absolutely learn. His type was a cipher: queer, cosmopolitan, managed.

Figures like Du Bois, Hurston, and Baldwin stitched freedom into cloth—not out of self-importance however imaginative and prescient. To revisit their type is just not nostalgia; it’s instruction, a reminder that to be Black and dressed is to be in concept, in course of, alive.

So who carries their vitality now? Prince did, for a time. In lace blouses and four-inch heels, he dressed like nobody else dared. However his genius was not in extravagance; it was in the best way he made area for others to decorate their truths, to deal with cloth as language and silhouette as assertion. Equally, Iké Udé’s self-portraits are much less about style than authorship, constructing a counter-history of Black class. Ekow Eshun curates type like a scholar curates concept. Solange Knowles lives in her visuals: chrome, cowries, material—none of it arbitrary. And Grace Wales Bonner doesn’t simply design however excavates. Her clothes are essays in cotton and wool.